11/04/2014

Doing business in India

An article of Les Echos (renowned French business newspaper) of 8/10/2014, by the journalist Patrick de Jacquelot, correspondant to New Delhi. Here the link to the newspaper.

An article of Les Echos (renowned French business newspaper) of 8/10/2014, by the journalist Patrick de Jacquelot, correspondant to New Delhi. Here the link to the newspaper.

Strong sensations strong and real dangers await companies that embark on the huge Indian market. Improving the business climate is one of the biggest challenges for the new Government.

“When we buy components in Bangalore to use in a plant in Hyderabad, 500 kilometers away, the cost of transport and internal taxes is such that it is sometimes more cost-effective to ship them from Bangalore to Europe and from Europe to Hyderabad”, are you told at the Indian headquarters of a big French IT company. “Of course, these are special cases, but in India every case is special!”

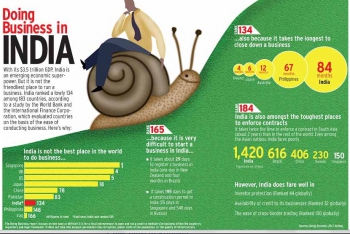

When the Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, launched with great fanfare on September 15th the campaign "Make in India", intending to convince industrialists from around the world to invest and produce in the country, it was not this kind of characteristics of the business life in India that he was thinking of. His speech was rather about the size of the market and its growth prospects. Yet among the big Indian bosses and foreigners invited to speak, many went beyond the mandatory tributes to the foresight of the new strong man of the India, and highlighted that working in the country is not a sinecure: infrastructure, labor, administration, workforce qualification, all these areas require to be seriously improved if the industry is to prosper, they respectfully suggested. The Prime Minister agreed, lamenting the position of India in the ranking of Doing Business* (134 out of 189 for the ‘ease of doing business’), established by the World Bank. The administration has been alerted to the problem by his care and the Government will address it assiduously, he promised.

There is a lot to do. Mid-September, three CEOs of leading multinational companies – the British Telecom operator Vodafone, the British petrol group BP and the carmaker Honda – have publicly criticized the problems they encountered in India. Last month, the annual ranking of the World Economic Forum** has put India at the 71st rank, a drop of eleven places over last year. As for the classification of the World Bank, an authority on the subject, even if the methodology is not free from criticism, it's particularly unflattering for the country. Not only is India badly placed (by way of comparison, it appears 40 places behind Russia and China), but it is located in the very last row in four of the ten sub-indicators which make the Doing Business Index: creating a business, obtaining a permit to build, paying taxes, legally enforcing contracts. There is an 'Indian paradox', says KPMG in a study devoted to the issue: “the country’s growth is one of the fastest in the world, but it is among the most poorly ranked by the World Bank”. And then the consultant enumerated the "critical problems" like "the difficulty to obtain land, inadequate infrastructure, lack of electricity, binding social laws and tax regulations, lack of governance and transparency, and the process to obtain permissions".

Surrealist remedies

As a matter of fact, active foreign businessmen in India don’t lack anecdotes about the difficulties they encounter in their operations, even if they do not express them openly. The difficulty in creating a business, for which the country ranks 179 on 189, is highlighted by all, as well as the problems arising in the day-to-day management of activities. The common practice of the joint-venture between a foreign company and an Indian partner is the source of serious difficulties. "Initially, it goes very well, says Delphine Gieux, lawyer of the firm UGGC, who has been advising French companies in their activities in India for ten years, but as soon as difficulties appear, because the "business plan" was overly optimistic, for example, radically opposed attitudes clash: the French partner will want to reinvest to play on the long term, the Indian one will want to cut costs to get back to the balance as soon as possible.'' Examples of cooperation that went wrong are legion, from Renault with Mahindra to SEB with Maharaja Whiteline. Other "huge constraints" put forward by the lawyer: those resulting from the exchange (partial) control. For example, she says, “it is prohibited for foreign parent companies to lend money to their Indian subsidiary for their current needs. It is very penalizing when there is a temporary problem.”

The problems of companies with the administration when it comes to obtaining a building permit (India's rank is 182 in this area according to the World Bank!) or the countless permits required in their daily life are legendary. The Ibis hotel of the Accor Group has just opened its doors in the Hotel City of Delhi airport with a four year delay. The reason: the police "discovered" long after the launch of the construction that in this zone of sixteen hotels terrorists could use the rooms located near the tracks to aim at aircrafts. Surrealist remedies have been considered, like the construction of twelve meter walls, until more realistic solutions were found. The creativity of the administration manifests itself in all areas. […]

In the field of taxation (where the India comes to the 158th rank), horror stories are also plenty. The best-known is the Vodafone one: the Indian tax authorities have been claiming for years billions of dollars in respect of the capital gains realized on a former operation. The Supreme Court considered this request of the tax administration totally unfounded, but the Government of the time did not hesitate to pass retroactive laws up to dozens of years before to support its claim and the case is still pending. The French group Sanofi has been subject to a smiliar investigation from the Indian tax authorities for its acquisition of a subsidiary of Mérieux. Overall, noted Sumit Khosla, CEO of the consultancy firm Accuracy in India, "the fiscal situation is difficult to understand, particularly indirect taxation which is very complex, even for specialists. It requires to work in a certain administrative blur, which Westerners do not like.

Winner-loser

The situation is even worse for everything related to legal proceedings to enforce a contract, domain where India ranks 186 out of 189 countries. There, says Sumit Khosla, “the problem is not the lack of a legal framework, India is a country of law and all the mechanisms are there. But the courts are completely congested and when there is a problem, it is forever!”

Beyond the indicators of the World Bank, doing business in India also involves cultural differences. The harshness of Indian behaviors in this area often surprises Westerners accustomed to more ‘civilized’ practices. "The main difficulty, according to the Manager in India of a French company in cutting-edge technologies, is that Indian businessmen do not know the concept of a win-win relationship. For them, there has to be a winner and a loser. So you have to be suspicious all the time of partners, clients, suppliers and collaborators. "Concretely, Delphine Gieux advises her customers to "always keep total control of the money circuit" in their Indian subsidiary. Which means that “ideally, the Chief Financial Officer should be an expatriate”.

A delicate point, finally: if is equally difficult to do business in India for Indians and foreigners, the first have a proven way to settle problems, especially as far as administrations are concerned: corruption. Foreign businessmen speak little about this issue that makes them deeply uncomfortable: they have not mastered the “bribing skill” and are generally formally prohibited by their manager to accept such practices. And thus delegate the dirty work to their lawyers or other consulting firms. But according to a survey conducted by KPMG*** on "key solutions to manage issues and grow a business in India" gives a clear answer: corruption is one of the most prominent ones.

In a difficult business climate, some are tempted "to go somewhere else", in the words of the manager of the India subsidiary of a French industrial group. During the summer, Carrefour and Auchan left the country. Last April, the Japanese pharmaceutical giant Daiichi Sankyo has put an end to its disastrous Indian adventure by reselling its subsidiary Ranbaxy. However, such instances remain rare. Vodafone, BP and Honda, the three groups who have recently criticized the problems of the business environment in India, are investing heavily. Because, in the end, says a French patron of Delhi, after listing everything that poisons your existence, "what saves this country is its size; you won’t find anywhere else the same potential figures.”

Suffice to say that the initiatives promised by Narendra Modi to facilitate land purchases, put the administration online, make labor laws more flexible or unify the indirect taxation will be followed very closely by the community of foreign businessmen in India. Without too many illusions about the ability of the Government to make these obstacles disappear. Is this so surprising? After all, the conquistadors who actually profited from the riches of the Eldorado are those who survived to poisoned arrows, jungle, wild animals and fevers.

* http://www.doingbusiness.org/rankings

** http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2014-15.pdf *** http://www.kpmg.com/IN/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/Documents/KPMG-CII-Ease-of-doing-business-in-India.pdf

08:00 Posted in Expatriation (in India and in other countries), Incredible India! | Permalink | Comments (0) | Tags: india, doing business in india | ![]() Facebook | |

Facebook | |